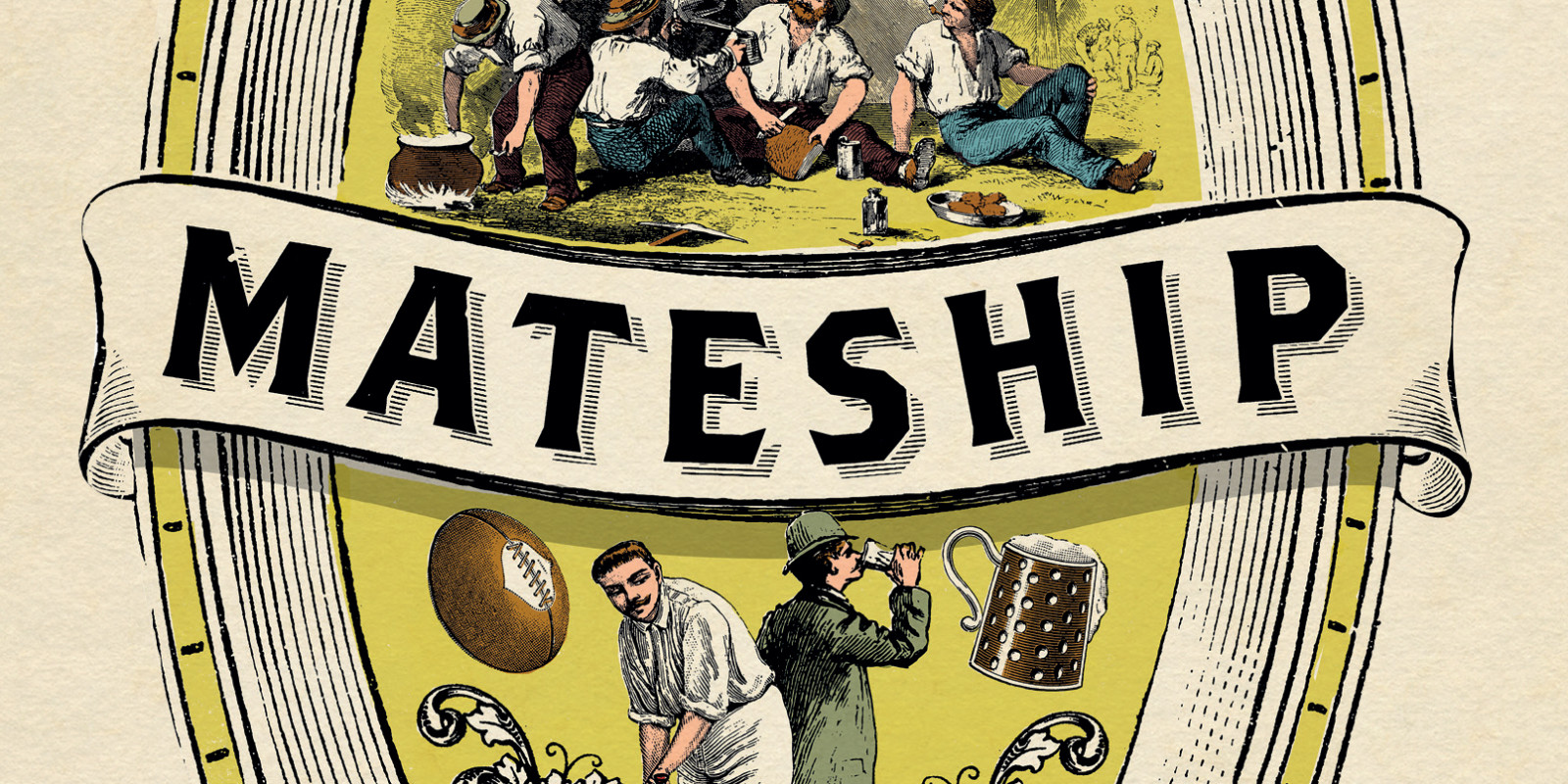

Mateship

Nick Dyrenfurth

Is mateship un-Australian? As I’ve shown, the term ‘mate’ possesses Old World origins. Likewise, mateship’s cultural roots clearly drew sustenance from northern soils. John Carroll insists that Australia’s mateship ethic, including the preference of working-class males for male company, was imported from Britain and Ireland. These established character traits were only reinforced by an experience of working-class life similar to that of home.1 But Carroll overlooks the fact that, in pre-1788 Britain, a mate could be any kind of friend. The term mate didn’t exclude women or heterosocial relationships — it was even applied to betrothed partners and spouses; but neither did mateship entail a heightened form of friendship. A couplet from Shakespeare’s 1594 poem ‘The Rape of Lucrece’ shows early mateship’s inclusive qualities through its praise of Collatine’s wife:

What priceless wealth the heavens had him lent,

In the possession of his beauteous mate ...

Pre-Australian mateship also transcended divisions of class and status. Kings and paupers alike could lay claim to sharing a mateship. When the Bishop of Worcester delivered a sermon for King Edward VI in 1535, he used the term in this neutral way, imploring the king’s subjects ‘to make a continual prayer unto God ... to grant our king’s grace such a mate as may knit his heart and hers’.2

Even when ‘mate’ became a favoured antipodean salutation during the early-to-mid-19th century, the word retained its former meaning in the mother country. The phrase ‘me and my mate’ was a common form of identification among the lower classes of London according to John Camden Hotten, a 19th-century lexicographer, and was variously applied to include one’s ‘friend, partner or companion’ of either sex.3 A play penned by Lord Byron during 1821 used gender-blind mateship in reference to the effeminate Assyrian emperor-king Sardanapalus:

The she-king,

That less than woman,

is even now upon

The waters with his female mates ...

Notably, ‘mate’ also referred to animals, and specifically to animals engaged in reproduction. This meaning — of a sexual coupling — would implicitly underpin future Australian visions of mateship.

In colonial Australia, mateship at once drew upon and deviated from its origins. The words ‘mate’ and ‘mateship’ changed from naming a casual association to describing a significant, even spiritual, male-to-male relationship. Why? As with many assumed national character traits, the answer lies with the 165,000 convicts dispatched 12,000 miles across the oceans to New South Wales between 1788 and 1868. In their pre-antipodean lives, the English among these outcasts, a high proportion of whom hailed from urban areas, likely used ‘mate’ as slang in the terms outlined above. The popular culture of the common people, particularly the dialect of Cockney London, was literally transported to Australia. Likewise, a version of ‘mate’ prevailed on the seas, as both a nautical title and egalitarian salutation between male sailors. Those convicts, English and Irish, who managed to survive the perilous eight-month voyage would have been washed by these rhetorical currents on board their floating prisons. Thus, by 1826, The Sydney Gazette and New South Wales Advertiser, the first newspaper published in the colony, had noted the practice of assigned convicts calling each other ‘mate’ — and the peculiar convention of ‘mate’ being used as a greeting to strangers.

That Australian mateship became a cultural phenomenon was due to a mix of nature and nurture. An extraordinarily unequal gender balance was a crucial formative influence. For more than 50 years after the arrival of the first fleet, Australia was a highly masculine land, what Henry Lawson later described as ‘no place for a woman’. Numerically speaking, of the 579 unwilling passengers aboard Captain Arthur Phillip’s First Fleet, men outnumbered women by three to one. Between 1787 and 1800, 5,195 male convicts, compared with 1,440 women, disembarked at Botany Bay. Women comprised just a quarter of the population for much of the early 19th century, and were concentrated in and around Sydney and Hobart.

The potential for ‘sexual disorder’ flowing from this gender imbalance so concerned authorities that, a year before the First Fleet set sail, Captain Phillip briefly considered and rejected Lord Sydney’s idea of kidnapping Tahitian women in order to sexually service soldiers and potentially provide marriage partners. In the absence of womenfolk, hard-living single males congregated in what historian Frank Bongiorno calls ‘little republics’, providing Australian masculinity with a ‘complexion still recognisable today’.

Masculine public culture grew apace. In the absence of formal amusements, gambling and drinking became wildly popular pastimes among both convicts and captors, as did testosterone- filled sporting contests such as cockfighting, bare-knuckle prize fighting, and horse racing. This isn’t to argue that such a culture didn’t similarly develop in other settler societies, notably New Zealand — but, in Australia, it acquired a particularly pungent masculine odour.