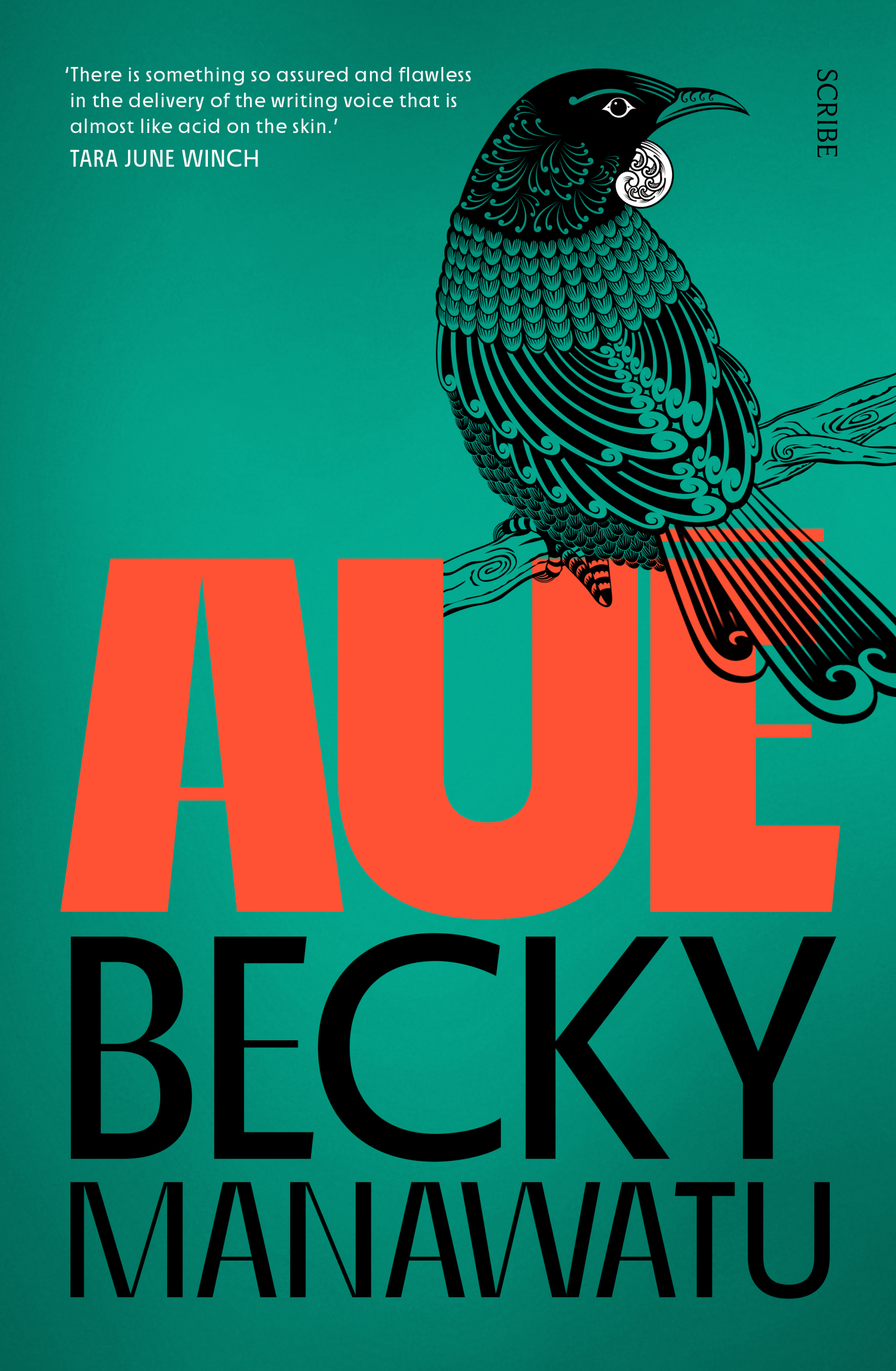

Aue

Becky Manawatu

Taukiri and I drove here in Tom Aiken’s truck. We borrowed it to move all my stuff. Tom Aiken helped. Uncle Stu didn’t. This was my home now.

Taukiri said that – ‘Home now, buddy’ – but he wouldn’t look at me. He looked around me, at the toaster, at a dead fly on the windowsill, at the door handle. He said something dumb, ‘You’ll love it, there are cows.’

You’re an orphan. I’m leaving. But cows.

He carried boxes into my new bedroom and pretended not to notice I hadn’t said a word since he’d packed up our house in Cheviot and driven me here. To Kaikōura. To Aunty Kat. To a place we sometimes visited but never stopped the night. He put the bed against the wall and the toys on the shelves, and lined up some of the books just like before. Not all of them. He left some of the books in the box, then he lifted it with a grunt and shoved it in the wardrobe.

‘Look after them for us,’ he said.

I didn’t answer. He didn’t care.

Taukiri looked around like he was happy now. ‘Just the same. Good eh.’

He didn’t say it like a question, so I kept my mouth shut.

‘I’ll be back as soon as I can, okay?’ But something in his voice didn’t sound like him.

I followed my brother outside. The others followed too. Tauk kissed me on top of my head then got in his car. He looked at the steering wheel, looked at the road ahead, plugged his phone in, scrolled through, hit the screen. Music roared from the car. Snoop Dogg.

Aunty Kat came over and folded her arms. Tauk turned the song down before Snoop said the ‘N’ word. Beth and Tom Aiken were there too. Tauk stared at Beth, then her dog, Lupo, like he was actually leaving me with them and not with Aunty Kat and Uncle Stu.

‘Be good,’ he said.

‘The driving. That coast, Taukiri,’ Aunty Kat said, her arms still folded, ‘just go easy.’

I hadn’t said a word in so long because I was afraid of how I’d sound. I hoped it would stop him, me not talking. Worry him a bit. But even when I didn’t say goodbye, he left.

He turned up Snoop Dogg as he drove off, which stung a bit.

We stood in the driveway. Me and Beth. Aunty Kat and Tom Aiken. Lupo was wagging his tail because he thought it was a happy thing. He didn’t know about goodbyes. At least this time I had a chance to say it. I just couldn’t. Uncle Stu wasn’t outside with us. He was drinking beer in front of the TV in the lounge of my new home. He’d had a long day, Aunty Kat said.

‘You and your brother look so different,’ Beth said as Taukiri’s car disappeared into the dust cloud it made for itself. Lupo had run off behind the car, chasing the spinning wheels, but then he’d seen a butterfly and decided to follow that instead.

Taukiri and I didn’t look different. We looked exactly the same. But I wasn’t talking yet, so I couldn’t argue with Beth.

‘You both have those eyes, though,’ she said, looking at mine. ‘But yours are sad. His are angry.’

Tauk’s car was on the main road. His surfboard on the roof made it look like he was just going to the beach for a surf, but something in my tummy told me it might be a long one.

‘He’s an idiot. You’re better off without him,’ said Aunty Kat, and she stomped off to the house.

Tom Aiken put his hand on my shoulder. ‘He’ll be back. Before you know it.’

I hoped he’d come and take me away from this shit-hole. I’d never used the word ‘shit’ before, but my mum and dad were dead and my brother just drove off with his guitar and surfboard, listening to Snoop Dogg, so there was no one around who’d care if I said ‘shit-hole’, or even the ‘F’ word. It was weird. I didn’t think I was happy about it. I’d heard Taukiri swear before, but not around me or Mum and Dad. Only when he was hanging out with his mates and he thought none of us was around to hear him. It’s actually funny how much you learn from hearing things you shouldn’t. I never thought my brother was much of a troublemaker, but I’d heard Nanny say he was. He sure was.

When Taukiri was gone we went to the bush to play.

I dug a hole in the dirt while Beth swung on a branch.

‘I dare you to eat a worm,’ I said. It surprised me that my voice sounded totally normal.

I flicked the dirt off a worm I’d found and hiffed it at her.

She caught it in one hand. ‘Right,’ said Beth, and she popped it into her mouth. Even let it dangle there a bit. It was wriggling around, but she didn’t care. She sucked it up so slowly I nearly puked. I told her to stop, so she spat it out. A bird swooped down from the trees and snatched it up.

‘Lazy bird,’ Beth said. ‘That worm was dug up.’

I decided to make a rule for myself – if I said a swear word, I’d have to eat a worm like Beth did.

We went to the swamp. Lupo started barking and Beth told him to shut it. When he stopped we heard a noise. A scuffle then a cry, like something was being hurt.

Beth pointed to the flax bushes, ‘Is that mum weka teaching her baby a lesson?’

There were two wekas busy doing something terrible.

‘That’s not what mum wekas do. Is it?’

Beth shrugged. ‘Let’s see.’

We walked closer. The strange cry got loud. The wekas were using their beaks to tear at the thing that was making the sound.

‘Bastards got a baby rabbit,’ Beth said.

In the muddy edge of the swamp there was a baby rabbit with skin hanging off, and legs going ways they shouldn’t, and the tiny bottom jaw torn away. It was crying like a baby. The wekas kept going at it with their beaks, their wings back behind them like seagulls do at washed-up fish or chips.

‘Oi!’ Beth yelled, and she ran towards them. They moved away, but not far. The baby rabbit tried to jump but it moved like it was made of the insides coming out of its belly. Its face fell into the swamp, and we watched it try to get air by lifting a nose out of the muddy water as if it was the heaviest nose an animal ever had.

Beth ran to it. She took her jersey off and scooped the muddy, blood-covered baby into it. The crying stopped.

‘Shhh, I got you. Those bastards. Eating you alive!’ Beth turned to where the birds were watching, grunting like winged lions. ‘Bugger off.’

‘What should we do?’ I asked.

Beth opened her jersey and we looked inside at the rabbit. Its back was like luncheon sausage, the face was half gone and the tiny top teeth were all that was left of its mouth. The legs had turned under, as if they were only fur now. Just soft fur and meat with no bones inside. It made me think of a toy, a toy made yuck for halloween.

Beth opened the jersey some more, and out the side of the rabbit’s belly a little bit of a yellow-bag thing was poking, and a fringe thing with teeth made from skin.

I threw up.

‘You weirdo,’ said Beth. ‘We need to help it.’

I wiped my mouth, ‘We can take it home and get some bandages. Plasters.’

I swallowed back more throw-up.

‘No,’ Beth said. ‘We need to help it die. It’s probably wishing it was never born.’

‘Rabbits don’t wish.’

‘What would you know, townie?’

Cheviot was actually country as, but I didn’t get into that with her.

‘If it can wish then take it home, bandage it, plaster it.’

‘It’ll be dead. Go get me a rock.’

Lupo followed me, sniffing around, wagging his tail the whole time. I found a big rock, and when I got back with it Beth put the baby down under a tree on a thick root.

‘Give it.’

I gave her the rock.

‘Don’t look if you don’t want,’ she said. ‘Ready?’ she said to the rabbit, which didn’t answer.

She lifted the rock up and I kept looking. I wished I hadn’t. Lupo barked and Beth wobbled. The rock came hard down on the rabbit’s back legs, making it cry like it had before, only more squealed.

The wekas started to grunt again.

Beth was crying. ‘I missed.’

Lupo barked. I kicked him in his guts to shut him up. He yelped.

Beth picked up the rock that had a bloody brown-and-yellow slick over it. The baby rabbit’s eyes said it was ready. Beth brought the rock down again. Right on its head this time. She sat down on the ground and looked at her hands. There were a few little smudges of blood on one palm. I sat beside her.

‘Are you okay?’

She didn’t answer, then stood up. ‘Don’t kick my dog ever again, townie.’

‘Sorry … I …’

‘You what? Wanted to help? I didn’t need it.’ She dragged her hand across her wet eyes. ‘This is a farm. And that was just a rabbit.’

She bent down and rolled the rock away. I looked at the squashed meat and guts and fur.

‘Now you bastards can have the damn thing,’ Beth said, walking away. The wekas tore away pieces of rabbit and ran into the bush.

She stormed off towards her house, with Lupo behind. I followed too, but she didn’t want me following her because she turned and stuck her tongue out. I stopped at the barn and cut across the paddock to my house.

To my house, like Taukiri said.

I went straight to the bathroom to wash my hands. I looked in the bathroom cabinet and found a box of plasters. I put one on my thumb, which felt good. So I put one on my knee too. Then I put one on my forehead, and another one on my other knee and one on my wrist. I wrapped one around my other thumb and I put one on the back of my neck, one on my chest and one on my cheek, and I put one over my belly button, and when there were no plasters left I stopped searching for places I was sore.

Uncle Stu grunted like a weka through dinner, chewing at the bones of the pork ribs Aunty Kat had made. He pushed his chair out, making a loud squeak when he had finished and kissed Aunty Kat’s head with grease around his mouth. He hadn’t noticed that it was my first night eating dinner with them and no one said a thing about the plasters that weren’t covered by my clothes. But what was the worst was Uncle Stu left his knife and fork leaning on his plate like he wasn’t finished eating and walked off.

My dad always lined his up in the middle of the plate, then took it to the kitchen. And if he’d kissed Mum with grease around his mouth, he’d have made a joke of it, and Mum would have laughed. Aunty Kat had closed her eyes and made her lips into a line.

After we ate I went to the bathroom to brush my teeth but couldn’t find my toothbrush. We’d left it behind in our bathroom. The one at our house. Taukiri packed, so really it was his fault that I had no toothbrush.

There was a soft toy on my bed. It looked like a baby rabbit before it was ripped to pieces and squashed by a rock. I threw it onto the floor. I climbed in my bed and tried not to look at it.

Aunty Kat came in to say goodnight.

‘I haven’t brushed my teeth,’ I grinned wide to show her. ‘Tauk didn’t pack my toothbrush.’

‘We’ll grab one tomorrow.’ She looked at the toy on the floor, ‘You don’t like soft toys, huh?’

‘Not that much.’

‘I’ll try to remember you’re not a little boy anymore. Sorry.’

I had a strange feeling, like when you’re in a deep bath and you pull the plug but don’t get out, just sit there getting heavier and heavier until the last bit of water twists loud down the drain.

Aunty Kat patted my head. ‘I suppose you’re also too big for goodnight kisses?’

I said, ‘Uh huh,’ even though I wasn’t.

She turned off my light and went into the hall. She put her hand on the hall light switch. I bit my lip.

‘I hope you don’t mind if I leave this on,’ she said. ‘Easier for Uncle Stu to find his way downstairs in the morning.’

‘That’s okay. If it’s easier,’ I said.

She left, but I didn’t think I’d be able to sleep, because I had meat between my teeth.

We are on a beach. Beth is holding the baby rabbit. It is in one happy piece. The beach is the same one where Taukiri was found. Bones Bay. A secret place. Up till now only three of us knew about it. Koro knows and he is in my dream. I am happy to see him. In my dream he is in one piece too.

We’re sitting around a campfire. Beth makes me and Taukiri laugh a lot, and I feel happy. Then we see something moving in the water. It swims towards us. It feels like something bad is about to happen and I’m scared. Beth and I cuddle into Taukiri. The rabbit too. Taukiri makes us all feel safe. Two figures come up out of the water. We soon see it is Mum and Dad. They come up the beach. They sit down by the fire. We all stay very quiet, like stones. Taukiri still has his arms around us; I can feel his fingers pressing deep into my arm. I ask Mum and Dad where they’ve been. They don’t know.

We go back to being quiet, but the roar of the sea is loud, and Mum and Dad are shaking and their skin is almost blue. They look like themselves. Alive. Just cold. Mum sits by Koro and puts her hand on his leg.

Nanny arrives. She’s wearing her favourite pearl earrings. She walks to Taukiri. They frown at each other. Tauk gives her a pūkana and I think she’s gonna belt him. But she says, ‘You left this behind,’ and swings his bone carving in front of her. We both have the same one. It is our thing – the bone-carving warriors.

‘I wanted to,’ he says.

I look down for mine and it’s not on the string around my neck.

There’s a toothbrush instead.

I woke up. Tried to go back to my dream to yell at Taukiri for saying he’d left his bone carving behind because he wanted to. But I just stayed there in my new room, with my eyes scrunched tight and furry teeth. A storm was crashing around outside, and rain was thuck-thucking on our tin roof, and the only thing I liked about all the noise the storm was making was it kept all those nasty birds quiet.

By the time she was talking to me again, Beth was making the place less of a S.H.I.T. hole and I was getting good at spelling swear words. A week after the baby-rabbit thing and the me-kicking-her-dog-in-the-guts thing, she arrived at my place while I was outside making a gun from a stick and said, ‘It’s pretty cool how close we live to each other eh?’

I’d tried to count the steps from my door to hers three times already, but every time I’d got distracted by a pūkeko or a weka. And if it wasn’t one of those birds that walked around like they owned the place, a cow would distract me, or I’d think I saw something shiny, like a pearl, and I’d have to stop and check what it was. Pick it up. Drop it again. Then I lost count. I didn’t know if I agreed with what Beth said – that we lived close. I thought if we really lived close, I wouldn’t forget so easily which step I should be counting.

Beth told me her mum had died too, so we had that the same. She was lucky, though, because she still had her dad. We were gonna ask if we could be brother and sister, which made me less sad that my real brother had left me there.

My aunty said Taukiri was probably never coming back. She said he would probably find his crackhead mother and they could ruin their lives together. I reminded her our mother was dead and she wasn’t a crackhead, whatever that was. She said nothing. I couldn’t believe she was so stupid that she forgot her own sister died. We’d all gone to the tangi. I’d watched Aunty try not to cry while Taukiri played his guitar and sang her favourite song ‘Tai Aroha’ – and not just because it had her name in it – for everyone.

I was going to be Beth’s brother, and then when we were old enough we’d change from being brother and sister to husband and wife, and we’d move to Auckland and buy a smart car. Beth said a smart car would be the best idea because parking in Auckland was supposed to be a B.I.T.C.H. A real S.H.I.T. of one. Beth swore a lot. It was lucky she didn’t have a rule about having to eat a worm every time or she would probably have turned into a bird herself.

Beth reckoned we only needed to have a smart car because we were not going to have kids. She said even though we’d be husband and wife she didn’t want to do what husbands and wives did to have babies. And she was right. It was disgusting. Lupo would fit in the smart car perfectly.

I liked Lupo, even though I’d kicked him. He was definitely dumb but really funny. Especially when he was chasing things. Normally whatever he was chasing outsmarted him.

My favourite thing about Beth was that she was a chatterbox. Aunty Kat and Uncle Stu didn’t say much funny stuff, only ‘do this’ or ‘do that’. Sometimes Aunty Kat asked, ‘You okay, boy?’ It was nice when she asked, but I thought she liked it best if I just said yes, and so I did, even when it was a lie. I wasn’t happy about lying either, or at least no one noticing it. Mum would have seen it. Stopped me in my tracks. I would eat a worm if I told a lie too, like my swearing rule.

To help.

To help me be a good orphan.

We were getting homeschooled together. Beth was supposed to start school last year but her dad forgot or something. Or maybe she’d tried it and got sent home too often for bad behaviour, so Tom Aiken decided she could learn at home. Something like that.

Beth changed her stories a lot. A lot, a lot.

My aunty offered for her to do some learning with me. The school was ages away, and counting the steps there would be really impossible. Aunty Kat said she wasn’t expecting to be raising a child out here in the wops. We should be grateful, she said.

It made me dizzy when I had to sit and learn the same things as before, when I felt like I didn’t need all that stuff anymore. It annoyed me that most of the time it was like nothing had changed. I liked that we used to learn Māori at my old school. I was one of the best in the class because Mum had already taught me and Taukiri how to count. She’d taught us the colours, some songs and every night we said a karakia.

Nanny said things too.

When I used to visit she’d come to the door and say, ‘Haere mai, haere mai, Ārama.’ And if I brought something awesome like the picture I drew at school of a taniwha she’d clap her hands and say, ‘Tino pai rawa, my moko!’ Sometimes Tauk made her mutter, and shake her head and say, ‘Whakamā, whakamā.’ And ‘Kei te pēhea koe?’ she asked me all the time, like all the time. And she didn’t care that I always answered the same, ‘Kei te pai ahau, Nanny,’ even when I wasn’t.

Taukiri once told me that it was okay that I didn’t know how to say anything else, because that’s all people wanted to hear anyway. And now I knew that was true.

Aunty Kat said she wouldn’t be teaching us Māori.

‘How could I? What do I remember? When do I use it?’

‘You’re brown,’ Beth said.

‘And?’

‘Mum knew some. Nanny and Koro know heaps,’ I said.

‘Living in a fairy tale,’ Aunty Kat said.

Beth sat up straight. ‘That’d be cool.’

‘Cool?’ said Aunty Kat. ‘With all the wolves and mean stepmothers and the dilemmas.’

‘What’s a dilemma?’ Beth asked.

‘Two choices with equally shitty outcomes.’

‘So don’t choose one. Stay put.’

‘That’s a choice too.’ Then Aunty Kat said nothing for a bit. ‘Maybe when Nanny’s not so busy she’ll teach you some Māori. I lost mine.’

In our classes Beth learned to write a lot more than her own name and words like cow, cat or P.I.S.S. and S.H.I.T.

My aunty didn’t understand how Beth had so much to say about things when she hadn’t been to school. Beth said her own aunty sometimes phoned her from Auckland and talked about life in the city, and that’s what got Beth talking. Aunty Kat said that was bull S.H.I.T. and the reason Beth had so much to say was from watching too much TV. Beth got sulky and didn’t talk for the rest of our lesson. But she came bouncing back, happy as a bird, the next day and acted like she hadn’t been peed off at all.

Later, when Aunty Kat was making a coffee, Beth whispered, ‘I’m still mad at her, but I really want to learn to write so I can get a big office job with my aunty in the big city. Then we can buy our smart car and apartment.’

I knew what an apartment was, but often Beth thought she had to explain everything to me. She said an apartment was houses stacked onto each other like boxes until they made a big tall building. In an apartment you could never be lonely, and if you ever ran out of anything you could just go ask for it from your neighbours. Which did sound cool. But when I got to thinking about it, I realised being in the bottom box, or even somewhere in the middle, would be C.R.A.P. because another box, and another, and all its stuff, and all the people inside, would be between you and the sky all the time.

I liked just having our tin roof between us and the sky. Sometimes at night it was scary to hear a storm, but I thought it was better being able to hear it. To know it was there.

Having more neighbours would be cool though. We just had Tom Aiken and Beth. Before I moved here we lived in Cheviot and I could walk to school, or to my friend’s house if I wanted to. Even to the Four Square for a lolly. Everything was close enough. Just a walk. And while I took it, I could still see my house when I turned back. A few other kids lived on our street. I sometimes wondered if they missed me. I sometimes wondered if they stopped at our old door and hoped I’d run out.

At night I missed Taukiri’s bedroom more than I missed my own. Sometimes I think I missed it more than I missed Taukiri. I definitely missed it more than I missed Nanny – and that was also a lot. I wanted to feel the way it felt to be in his room.

Night-time was the hardest for me. Without Mum and Dad. Without Taukiri just down the hall. Aunty Kat read to me, but it wasn’t the same. It was like eating sugar when you want a lolly. That’s what I could compare it to because when I asked Aunty if we could go for a drive to buy a bag of lollies, she laughed, and said there was not a chance. She told me if I needed a sweet that bad I should eat a bit of sugar. So I did. I sat on the kitchen floor with a bag of Pam’s sugar and shovelled spoons and spoons of it into my mouth. Then I lay on the couch with a sore tummy and head for the rest of the day. And it didn’t even taste good.

Nanny kept a jar full of lollies at her house. Sometimes she even had bags of Eskimos or Pineapple Lumps. It was strange I hadn’t seen her since I’d been at Aunty Kat and Uncle Stu’s. When I had my real life – not this one that felt like something I might wake up from – I saw my nanny at least once a week. She came for dinner all the time and always brought me a pressie. I could call her day or night for anything, she said. Since I came here I’ve called her house one hundred times already to tell her she needs to get Taukiri to come back. But she doesn’t answer.

I called Taukiri’s cellphone three times the day he left. I called it three times the day after, and I’ve called it at least three times each day since. It only rang twice. Now it goes straight to answerphone. ‘Sup, this is Tauk’s phone. Don’t check voicemail, so send a text.’

I didn’t tell Aunty Kat I was calling Tauk though. If she saw me using the phone she just sighed. ‘Nanny’s busy, Ari. Stop calling. She’ll call you back when she can.’

My mum used to say things happen in threes. Once I fell off my bike three times in one week. ‘Everything happens in threes, be more careful,’ she’d said. But that was just on the second crash, so I was never sure if I crashed the third time because of the rule of threes, or if I just wanted to get the last one out the way.

Mum kissed me and put plasters on the five places I was bleeding and I put one more on a bruise.

I thought of Taukiri away from here, driving his car whenever he wanted, music so loud. He’d left a long time ago already, he must’ve made it safely to wherever he’d gone. But I couldn’t help going over things that had already happened, trying to figure out what had been done in threes and what hadn’t.

Mum was dead. Dad was dead. Did that mean someone else had to die too? Or could that rabbit count as the third?

Today, I counted up seventy-four plasters left from the box of a hundred I found, and told Aunty Kat we should always keep more than one box in the house. We lived in the wops, after all. It seemed like she didn’t hear me so I snuck into her handbag and put ‘plasters lots’ on her grocery list.