A Witness of Fact

Drew Rooke

I stand in the viewing gallery, scanning the large, bright room on the other side of the window. It is quiet and clean; it is mid-afternoon, and, like most days, the daily case list was completed earlier in the morning. The blue-linoleum floor has been hosed down and scrubbed, leaving small puddles of water to dry beside the grated steel drains, down which had flowed blood and other bodily fluids only a couple of hours earlier. Neatly laid out on the stainless-steel benchtops are sterilised and ready-to-use scalpels, scissors, forceps, and ladles, an array of shiny silver that reflects the fluorescent lights beaming down from the ceiling.

A pair of large, heavy-duty shears used for cutting through ribs hang on one wall. Nearby is a magnetic knife strip full of knives of different sizes and styles — curved, straight, long, and short — with different-coloured handles, similar to what you would see in a commercial kitchen. At each of the three examination bays is a manoeuvrable medical light that looks like a giant eye, a set of scales for weighing major organs, an electrical socket for any power tools that will be needed during autopsies, and a whiteboard for recording the weights of various organs.

The lightbox for viewing X-rays has been switched off, and at the back, next to the doorway of an isolated dissection room used for infectious or high-risk cases, is the entrance to a cool room with space for up to seventy bodies. At certain times of the year, such as in the peak of summer, when sudden deaths are especially common because of extreme heat, it is completely full.

Located on the ground floor of Adelaide’s Forensic Science Centre, an imposing brutalist building in the middle of South Australia’s capital city that bears its name in huge steel lettering on the concrete façade, and that towers above the neighbouring stone church, the mortuary is both a macabre and profound place, one ‘where death rejoices to come to the aid of life’, as an ancient Latin phrase common in many mortuaries around the world has it. It is operated by Forensic Science SA (FSSA), an agency within the South Australian Attorney-General’s Department responsible for providing independent forensic science services throughout the state. Split into four separate scientific divisions — pathology, toxicology, biology, and chemistry — FSSA is guided by the motto that is displayed in the building’s lobby: ‘Science Safeguarding Society’.

Prior to the opening of the Forensic Science Centre in 1978, autopsies in Adelaide were performed in a small stone Victorian cottage that was located amid the tombstones of the nearby West Terrace Cemetery. Long destroyed, the old mortuary was a grim place: it did not have proper protection from the wind, dust, or flies, nor adequate ventilation, nor sufficient storage capacity. Bodies were often just piled up on the floor in a corner.

As well as being far more advanced and hygienic than its precursor, the modern-day mortuary is also much busier: each year, roughly 1,400 autopsies — also known as post-mortem examinations — are performed here by order of the state coroner in cases of unexplained or unexpected death in order to ascertain, as closely as possible, when and how a person died.

I have travelled from my home interstate to visit it for one reason: I want to see where Dr Colin Manock spent most of his time as South Australia’s chief forensic pathologist, a position he held from 1968 to 1995. In that time, he played a significant role as a medico-legal expert in the criminal justice system: according to his own estimate, he helped secure more than 400 convictions, and performed approximately 10,000 autopsies.

Until recently, I had never heard of Manock. But he has been a notorious figure in Adelaide ever since a few local journalists and legal experts started digging into his career and some of his cases more than twenty years ago. And as I began to understand the reasons for his local notoriety, I was amazed it was not more widespread — and was very eager to find out more about him.

He first came to my attention by chance in early 2019 when I saw a post on social media about a man who had been in prison for murder for more than thirty years but claimed to be innocent. Manock’s expert scientific evidence had been crucial to the prosecution case against this man, but its validity had since been seriously questioned by numerous experts who had reviewed it. In fact, some of these experts had said there was no scientific basis at all for Manock’s evidence.

I was immediately intrigued and had many questions about the case. Was this man innocent, as he claimed? And how had Manock gotten it so wrong, if indeed he had? Had he made a genuine — albeit embarrassing — error, as all of us are prone to doing at some stage? Or had he made up his evidence?

If he had made up his evidence — or, at the very least, exaggerated it — what was his motivation for doing so?

But as I looked into the case more, I quickly learnt that there was a lot more about Manock’s life and career that was equally — and, in some cases, even more — intriguing, and worthy of further investigation. Indeed, it turned out that the case that had sparked my interest in Manock was just one of several in which he had been found to have made major mistakes — some of which had likely resulted in criminals walking free, and innocent people being imprisoned. Looked at together, the mistakes formed an alarming pattern and pointed to serious problems with the way Manock worked, but were not hugely surprising — considering that, it turned out, there had been serious questions about Manock’s qualifications and suitability for such a senior position from the very beginning of his long career.

What was surprising, however, was that the full extent of the scandal which Manock was at the centre of still remained a mystery more than two decades after it had first been revealed. And even more surprising was that there was little desire among those in power to fix this by instigating an inquiry into Manock in order to determine exactly how he had been able to retain his job for so long despite his error-riddled record, and whether or not he had made any more serious mistakes in other cases he had been involved in, in addition to those that were already known about, which might have resulted in miscarriages of justice.

The scandal, I came to realise, was thus about much more than the questionable conduct and mistakes of just one forensic pathologist; it was about an entire legal and political system which had failed — and was still failing — to properly address or even acknowledge its flaws and to ensure that the interests of justice, science, and truth were upheld and protected.

I was as keen to understand this systemic failure as I was to understand Manock himself.

But the more I researched the scandal, the more I realised that it was about even bigger issues, too — and the more my interest in it grew.

Although it was hyperlocal, it was in many ways a microcosm of the scandal that has recently erupted around Australia and around the world about the questionable veracity and accuracy of many forms of forensic science that have long been utilised by criminal investigators and relied on in courts by prosecutors to secure convictions.

And on an even deeper level, the scandal also seemed to me to be a timely reminder of the importance of remembering ‘the infinity of our ignorance’, as philosopher Karl Popper put it, and served as a cautionary tale about what he believed to be among the ‘real dangers’ to the progress of science: ‘lack of imagination (sometimes a consequence of lack of real interest)’; ‘a misplaced faith in formalisation and precision’; and ‘authoritarianism in one or another of its many forms’.

~

Anyone wanting to find Manock while he worked as South Australia’s chief forensic pathologist usually only had to look in the mortuary at the Forensic Science Centre. But while he could once be easily found in the room I’m now looking into, he is a very elusive figure these days.

I had naively assumed that I would have little trouble contacting him. For one thing, Adelaide — or Tarntanya (The Place of the Red Kangaroo) as it is known to its traditional owners, the Kaurna people — is a pretty small place. And, as Claire O’Connor, an esteemed criminal barrister who has lived there for more than four decades, told me, the legal fraternity that Manock had links to for so many years is ‘even smaller’.

‘Many lawyers today who are successful in practice are the sons and daughters of judges, silks, and partners in law firms,’ O’Connor explained.

For another thing, Manock has been the subject of many local media reports over the previous two decades. Indeed, it seems that most people in Adelaide are at least familiar with his name, even if they know nothing else about him.

Yet nobody I initially spoke to — including several of Manock’s former colleagues, some of Adelaide’s most well-connected lawyers, and experienced local journalists who had reported extensively on the controversy surrounding his career and many of his cases — could provide his contact details or any information about his whereabouts. Many had heard that he had recently been suffering from serious health problems, including dementia, but no one knew for sure if he was still alive.

Although it was unlikely, I thought that maybe he had died, and nobody had noticed. Or perhaps he simply did not want to be found.

My hopes of finding him if he was still alive were boosted one day when I visited a home address of his listed in an affidavit that he had provided to a Medical Board of South Australia hearing in 2004. Although I had been told that he no longer lived there, I decided to visit anyway in case someone residing there or any of the neighbours had a lead to him.

Disappointingly, the address was an empty construction site. But as I stood before it, an elderly woman pulled into the driveway, directly opposite, of a pretty cream house with a well-manicured garden. She looked at me suspiciously as she stepped out of her car, but grew friendly when I walked over and introduced myself.

The woman told me that she had lived in the same house for decades, and that Manock had moved out around nine years earlier. She recalled him as ‘friendly’, and said he ‘kept to himself a lot’. She also remembered hearing many ‘bizarre and disturbing’ rumours about him — none of which she wished to repeat.

When I explained that I was having trouble contacting him, she thought for a moment. Then her eyes widened with excitement, and she told me to wait a moment before dashing inside her home. Minutes later, she reappeared, holding a small white business card that, she explained, Manock had given her when he’d moved to a new house. At the time, she had simply thrown it into the bowl in which she keeps all the business cards of her friends and acquaintances. She said she had forgotten about it until now. It read:

Dr COLIN H. MANOCK

M.B, Ch.B., F.R.C.P.A., J.P.

Forensic Pathologist

On it were Manock’s complete contact details: two phone numbers, an email, and an address.

But later I discovered that the phone numbers on the card had been disconnected, the email I sent bounced, and once again I found myself chasing Manock through suburban streets, arriving out the front of a single-storey brown-brick house on a leafy street in Adelaide’s eastern suburbs. It was, however, unoccupied. Electrical wires were hanging from the tiled roof, sun-bleached catalogues were sticking out of the white letterbox, and weeds overran the front yard. In the windows, signs warned that trespassers would be prosecuted. ‘SMILE! YOU’RE ON CAMERA’, read one. Before I left, I slipped a note under the door, asking anyone with any information about Manock to get in touch.

I was not hopeful of a response, but the next day my phone rang. It was the landlord of the brown-brick house. Happy to chat, he told me that Manock had vacated it at the end of 2016. ‘He was very friendly,’ the landlord added, recalling that Manock ‘liked shooting guns’ and had a press for making bullets in the garden shed. ‘He had lots of lead weights, and would melt the lead down and pour it into the mould with the bullet ends and press them into the shells.’ Like the previous neighbour, this landlord also knew about the rumours that circled Manock, and said he seemed indignant about them. ‘It was like he believed that he was the victim and that everybody had it in for him.’

The landlord also remembered Manock’s wife — a professional dominatrix from Adelaide named Morgan Gabrielle Jaya Cox, or ‘Mistress Gabrielle’ for short. He did not remember Cox fondly, however. He said she ‘frightened the crap out of me’. He also thought the relationship between her and Manock was ‘very strange’. She was considerably younger than her husband; one time when the landlord was visiting the property, Manock pulled him aside and showed him a picture on his phone of Cox, who was scantily dressed, and said proudly, ‘Have a look at my wife.’

The landlord thought Cox might be able to help me reach Manock, but he had no way of contacting her. So I began searching online for her contact details. As I did, I discovered that the landlord had good reason to be frightened of Cox: in 2018, she was found guilty of assault after she had placed another woman in a headlock and punched her several times in the head at an adult event that had been held in Adelaide two years earlier. Outside the Magistrates Court after the verdict was handed down, Cox claimed she had been targeted by authorities ‘because I’m beautiful, young, and a dominatrix’.

Online, I also discovered videos of Cox in which she takes viewers on a virtual tour of her fetish parlour in a secret location in the city. A tall, muscular woman with broad shoulders, pale skin, and long jet-black hair, she appears in one video dressed in a tight red-latex dress with matching gloves. ‘Come with me and I’ll show you my medical suite,’ she says to the camera in a soft, husky voice. She opens a door and walks into a room that, in many ways, resembles the mortuary at the Forensic Science Centre. There are stainless-steel benches and medical utensils, electrical devices, and a gynaecological examination table illuminated by large medical lights. Next to the table is what she calls her ‘pièce de résistance’: her autopsy kit. Seeing this, I wondered if it had once belonged to Manock, and if he had taught her how to use the instruments that were inside.

Eventually, I found a phone number for Cox, and decided to give her a call. I was tense as the phone rang and she answered. But her friendly, chatty demeanour calmed me; she told me she was still happily married to Manock and that she thought it was ‘hilarious’ that she was now his only point of contact. Although she would not disclose the whereabouts of her husband, she asked me to email her more information about the book I was working on, and said she would check with Manock to see if he was interested in being interviewed.

Eleven days of silence passed before I emailed her again to check if she had any news. She responded a short time later.

‘Colin said to tell you that he’s not interested in doing any interviews at this time,’ she wrote, ‘and to proceed with caution when dealing with his name …’

I was disappointed by this response: without speaking to or even meeting him, I knew there would be much about him that I could never know or understand. But I was not deterred by this, nor by the thinly veiled defamation threat. Thankfully, there was a lot more material I could draw on in order to piece together the puzzle of his life and career — including old newspaper profiles of him from when he was appointed South Australia’s chief forensic pathologist, several different versions of his resumé that he prepared over the years, many of his autopsy reports, transcripts of his oral evidence in a number of cases and hearings he was involved in, and interviews he had given to journalists in the past.

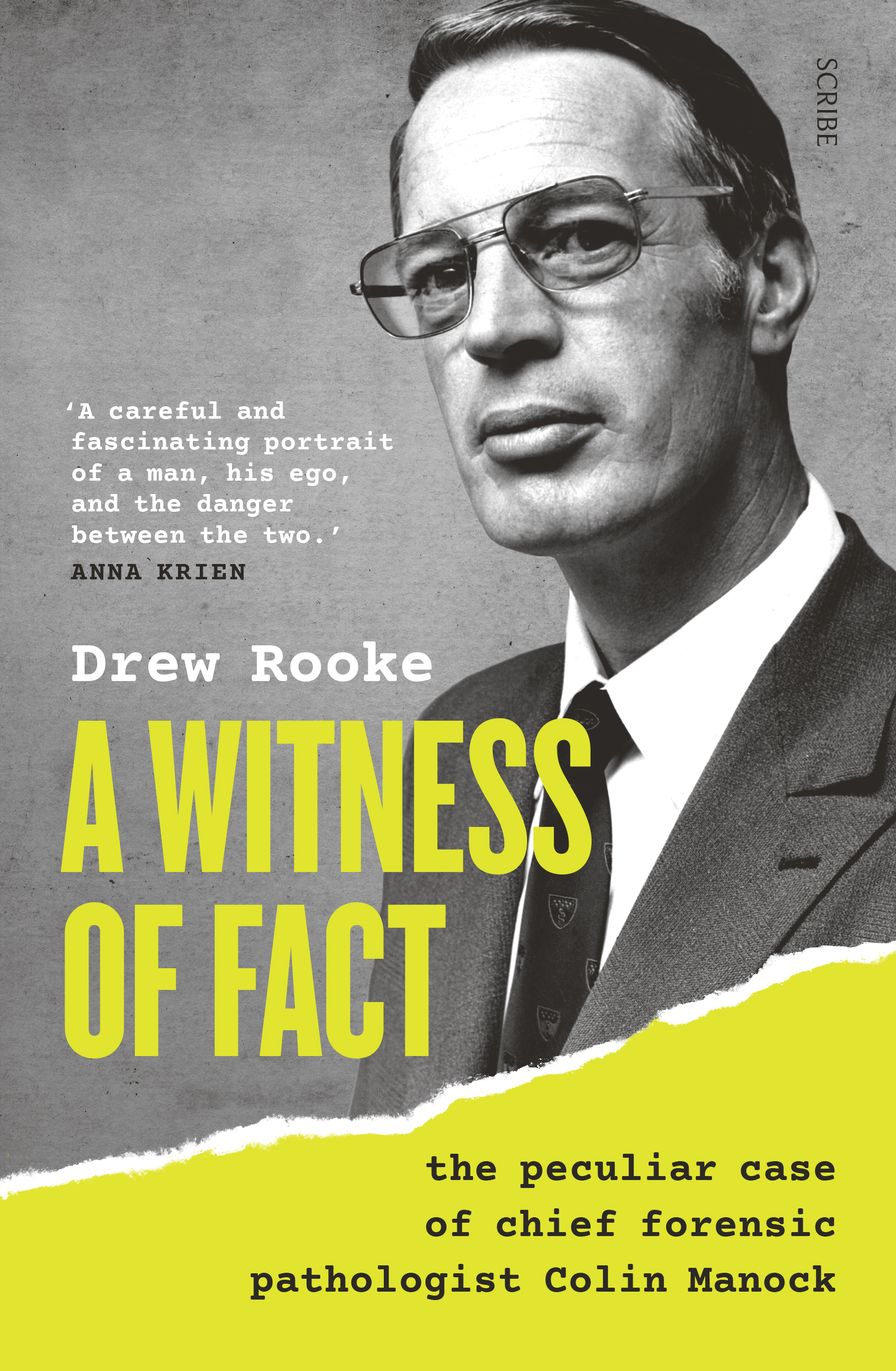

In one interview with the ABC’s The 7.30 Report in December 1991, Manock explained the value of his work. In the footage, he is fifty-four years old and of average height and build. He is seen striding through the mortuary at the Forensic Science Centre, passing two metal examination tables, towards the camera. His long, narrow face is clean-shaven, and his short white hair is neatly combed over to the left of his high forehead. He is wearing brown dress shoes, grey trousers, and a tailored mauve shirt with the sleeves neatly rolled up to his elbows. A watch is strapped on his left wrist, and his dark eyes look through a pair of gold-rimmed, aviator-style spectacles that sit on the bridge of his large, sharp nose.

When he reaches the camera, he pulls on a disposable green surgical gown, as if he is about to perform a live autopsy, and says, ‘There are very good reasons for carrying out post-mortem examinations, and that is that you cannot assume from clinical history that you know what the cause of death is going to be.’ He speaks authoritatively and has a proper British accent with faint Lancastrian undertones. Every ‘s’ syllable comes out as a hiss.

While effortlessly tying the strings of the gown around his neck and lower back, as he would have done hundreds of times before, he continues: ‘And a series of post-mortem examinations following a medical death certificate showed around 50 per cent were wrong, and of those, about 20 per cent were even in the wrong system.’ He emphasises this last point. He leans slightly forward, widens his eyes, and huffs, as if to say, How bad is that?

But it is only now as I stand in the viewing gallery looking into the mortuary where Manock spent so many of his working hours that he really comes alive in my mind.

I imagine him busy at work just on the other side of the window. He is examining a body at one of the examination bays, trying to find and decipher the clues to how the person laid out in front of him died. A natural death? An accident? A suicide? Or something more sinister? He is dressed in surgical garb and is speaking into a Dictaphone — as is his practice — as he works to create a verbal record of what he finds. I picture him being relaxed while he handles and dissects the organs, at ease in the company of corpses. Once he has finished, once he has solved the riddle of death in front of him, he pulls off his bloodied rubber gloves while his assistant stitches up the body and wheels it away before bringing in the next riddle for him to solve.

As I imagine this, I remember his earlier message to me, and can’t help but wonder how often he reminded himself to proceed with caution when he was dealing with the dead.