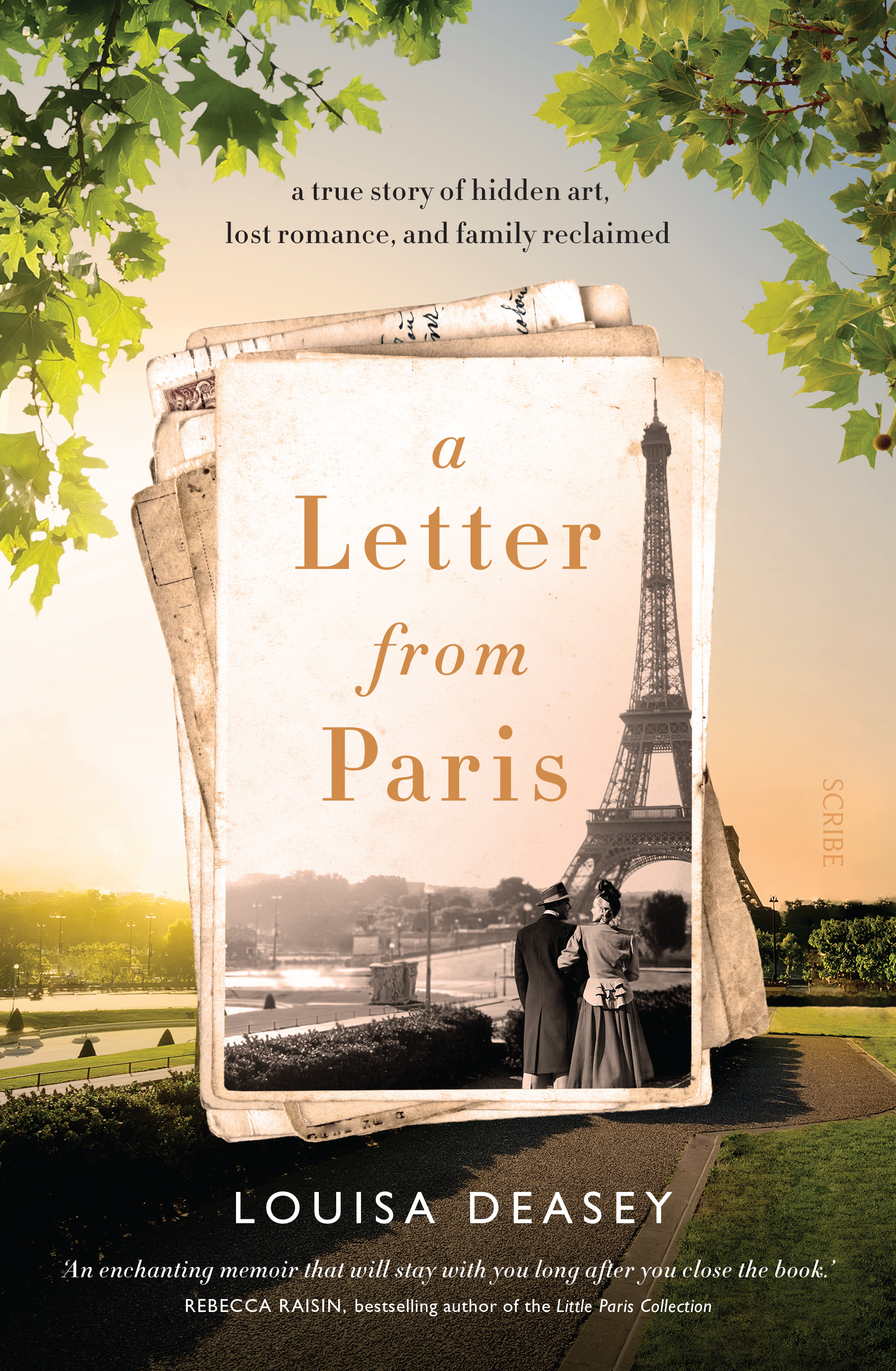

A Letter from Paris

Louisa Deasey

When dad died in 1984, on a hot Saturday night in February just before my seventh birthday, it was the only time I ever remember seeing mum cry. I’d slept in my new leotard the night before. Paleblue polyester with stripes of gold, it was so prickly in the summer heat. Mum had bought it for the gymnastics classes I was about to start. So I wore it to bed — ready for a cartwheel on a high beam, not falling asleep on a sticky Australian summer’s night.

How odd, the things we remember.

He had a blood clot, mum explained, after hanging up an early morning call from the hospital. It travelled to his heart, she said between tears.

It took me a while to comprehend that he wasn’t coming back. That he’d gone somewhere I couldn’t visit. That his death meant no more Friday-night drives past Skipping Girl Vinegar dancing in her red dress along the way to his big rambling house in Surrey Hills full of books, papers, the clack of his typewriter, that musty smell of dust and pipe tobacco, his cheeky grin.

And I’d never really know who he was.

I did get hints that dad was remarkable, but I also got hints that he was wild. There was the sense that he was inexplicable, someone I should perhaps be ashamed of. The black sheep of the family. I gathered he’d lived a life that was far from normal — or even acceptable — to the family and the time in which he was born. The only obituary I’d ever seen, printed in the Geelong Grammar quarterly The Corian, held a list of his ‘unfinished’ published work. I forgot all the rest.

Casual comments can create an entire story a child builds up around a parent — and the story’s even stronger when you can’t remember who made the comments or where or when.

He squandered three fortunes …

He wasted his talents …

What Geelong Grammar–educated man drives taxis … ?

The tone I absorbed was one of disapproval and shame.

The story was that he was impulsive, that he ‘wasted’ his money on writing and travel and never finished anything, that he should have been more stable, should have made more sense. He was ‘difficult’, possibly a bit of a lunatic. What hurt the most was the word ‘amateur’ — where had I read that? Was it from Geoffrey Dutton’s memoir, Out in the Open, or Alister Kershaw’s Hey Days? They were the only two books I’d ever found that mentioned dad. Or was it from the obituary in The Corian?

Denison conformed neither in his behaviour nor in his intellectual attitudes or aesthetic tastes, according to his obituary, written by prominent businessman Sir Robert Southey. A paragraph from writer and editor Stephen Murray-Smith was also included, claiming that dad was caught up somewhere between the Celtic twilight, the South of France, and Ayer’s Rock … None of it had made any sense to me as a child.

The effort of packing up dad’s house, and his papers, was enormous, and it took mum over a year. She always had an anxious, heavy face after he died, tight with remembering. The complication of his boxes and paperwork made her so sad. I learned not to say his name, sensing a guilt so complex I might make something explode by asking for details.

Two or three memories of dad stayed with me, like visions from a dream that quickly disintegrates when you open your eyes. I had to write them down to keep them safe.

The first was when dad turned up at my primary school, pulling up in his taxi outside the spot in the playground where I was playing with my friends. It seemed so miraculous that he’d found me, in all the giant playground and secret places I could have been hiding. I usually only saw him every second weekend, or birthdays, because by then he and mum had separated.

Dad, grinning with sparkly eyes, was holding something in his hand for me and strode from his taxi to the school fence to pass it over: a box of chocolate Smarties. It might as well have been a Willy Wonka bar with the golden ticket. Chocolate was a special treat — especially when given randomly, and in the middle of a school day.

‘Make sure you share them, Louie.’ He grinned, and waved goodbye.

Another time, he turned up unexpectedly with another gift — a soft toy bunny rabbit he must have seen in a shop and bought on a whim.

‘Where is Lou?’ he said theatrically, standing behind the flyscreen door at mum’s house in North Carlton, pretending he didn’t know it was me because I’d had my hair cut.

‘It’s me, dad!’

‘Don’t forget to give Lou her gift!’

And then — the broken bottle.

We made the trip to the shops near his house. He always had a glass of red wine with the Sunday roast, which we’d eat in his kitchen after church at 3.00 p.m. He called it ‘Sunday dinner’, and it was one of his favourite rituals.

He walked out of the shop with a bottle wrapped in paper, and realised he’d left something inside.

‘Hold this for me, Louie?’

Inevitably, I dropped it. Red liquid and broken glass covered the footpath, and the smash made me so frightened that I ran down the street. Dad’s long legs caught me within seconds.

The look of fear and sadness in his eyes was worse than any anger I’d expected over the broken bottle.

‘Lou! Why are you running?’

‘I smashed your wine, dad.’

‘There’s always more wine! But there’s no more Lou!’

And then he died.

No more dad.

It was late on Saturday night when Coralie first contacted me. Despite a sudden summer storm, my inner-city apartment was stifling. I’d returned from a friend’s house for dinner. An amazing cook, she’d made a small group of us seafood and salads, and we’d talked into the night as we waited for the storm to settle. Dinner at Carmen’s was the highlight of an awful week.

In the space of seven days, I’d attended a funeral, been to the emergency ward, and had to call the police because my downstairs neighbour had gone off the rails.

I’d quit my job at the University a fortnight earlier after an impossible situation, and the prospect of starting from scratch depressed me. The job had been so ideal when I’d started, and ended so awfully, leaving a sad hollow in my stomach, a resistance to giving anything else my all.

I wanted to write, maybe freelance again — but I had to come down from the year-long stint at the University, the disappointment I felt at how that had all turned out. There was no space in my head to plan and dream — everything felt a bit scary. I wondered if there was something wrong with me, for not being able to ‘hack’ the situation at the University, if only to keep earning a regular income.

I felt caught between worlds, unsure of who I was or what I wanted, restless but tired. Anxious and disorientated. Disappointed in myself, somehow.

I sat trying to remember who I was, and what I wanted — if I could trust myself to want something again.

A Facebook ‘message request’ appeared on my phone as my neighbour’s shouts of abuse reached up from her balcony below.

30 January 2016

Hello Louisa,

I hope you won’t mind me contacting you in such an unsolicited way.

My name is Coralie. I live in Paris, France. My grandmother, Michelle Chomé, recently passed away and we found in her apartment a stack of letters written during the year 1949 to her parents in Paris. At the time she was an au pair in London.

In these letters she speaks of an Australian man called Denison Deasey. She met him on the train to London — he was there that same year with his sister. It seems he took her on some very special outings around London … she was very smitten with him.

Are you related to Denison Deasey? Again, I hope I am not disturbing you in any way …

Denison. His name was a shock and a surprise, like the stranger who typed it. I hadn’t thought about dad on any conscious level for such a long time. His story was a scar that still tugged and pulled whenever it was exposed.

Seeing his first name and reading of him was an unexpected visitation. It brought him back, it called him in. I realised just how much I missed him without knowing him, how much I still wanted to know.

I returned to that long-familiar longing, the knowing but not knowing, the unfinished story. Unsure what to hope for, unsure if I should.

I’d only reactivated my Facebook account that morning after a two-week break, to stop getting alerts from University pages. Even odder, I’d then changed my profile picture to an old picture I’d taken at the Louvre, an unexpected pang to return to France having surged over me as I sat up in bed after waking. I’d been trying to think of something that excited me, since I was feeling so lost.

I have to go to Paris again this year, I’d written in my diary.

But here was a message — from Paris. It seemed like a confirmation. I had to get back there. But how?

Michelle met Denison on the train to London after the ferry from Dover. They went on some very lovely outings in London … they went to Westminster Abbey to see King George and Queen Elizabeth, they saw a John Gielgud play so she could learn better English … she describes him as handsome and charming … she adored him!

My family was wondering if you have a photo?

I picked up a photo from my bookshelf, the one and only picture of dad and me, sitting in a park somewhere in Melbourne. He’s holding me in his lap, looking away from the camera into the distance, his pin-striped shirt rolled up at the sleeves.

He must have been in his early sixties. It was 1981 and I was four. He had the look of worn fatigue and wistfulness, like he always did in in my memories. His grey hair was smoothly scooped to the side of his face.

The yellow undertone of illness. He probably had cancer when that photo was taken. I wonder if he knew it … ?

I never could imagine dad as a young man. All I’d known him to be was old, sick, the holder of history from an era I would never fully understand. I’d never asked mum — gathering, from their painful separation and then his death, that it hurt too much and that she felt guilty about leaving him when he’d been so close to the end. Of dad’s six siblings — three brothers and three sisters, all older, though his brother Irwin had died as an infant — only two were still alive when I was born, and they were aged in their late sixties. Both were now dead. I’d never known my grandparents — they, too, were dead before I was born.

But here was Michelle — a woman in France, who until just yesterday had been alive.

And there were stories to tell.

Perhaps Michelle had spoken about my dad, for how else had this family been curious enough to contact me? Who was the ‘family’ Coralie meant in her message? Her message seemed to imply dad was someone special.

What frightened and excited me at the same time was that this stranger in a foreign country was able to tell me a beautiful story about my own dad.

From the moment I read Coralie’s message, I knew I had to meet this family in France.

Coralie’s face on her Facebook profile was pretty, sunny, light. Her face pressed up against her husband’s, she was holding a little baby and smiling.

The Louvre, behind me in my own profile picture, only changed that morning, seemed almost like a cosmic joke. I thought of the night it was taken — the night, ten years earlier, when I’d walked for hours across Paris to try to find Gisèle.

Gisèle and dad had lived in France for a time and then in Australia. At some point, Gisèle had returned to France, and dad had met mum. Like everything else about dad’s life, I didn’t know the timing. All I knew was that Gisèle had loved dad, and they’d been together ‘a very long time’, as mum had once said.

And because we were his children — Gisèle had loved us, too.

Was this dad reaching out from beyond, offering up a gift, a clue, a message? Imploring me to search one last time — if not for Gisèle, then at least for him?

I felt like a rare bird had landed on my windowsill.

A chance, an opportunity.

Something very fragile.

I started to reply before it flew away.