Related content

AUTHOR

Niki Savva

Niki Savva is one of the most senior correspondents in the Canberra…

Discover

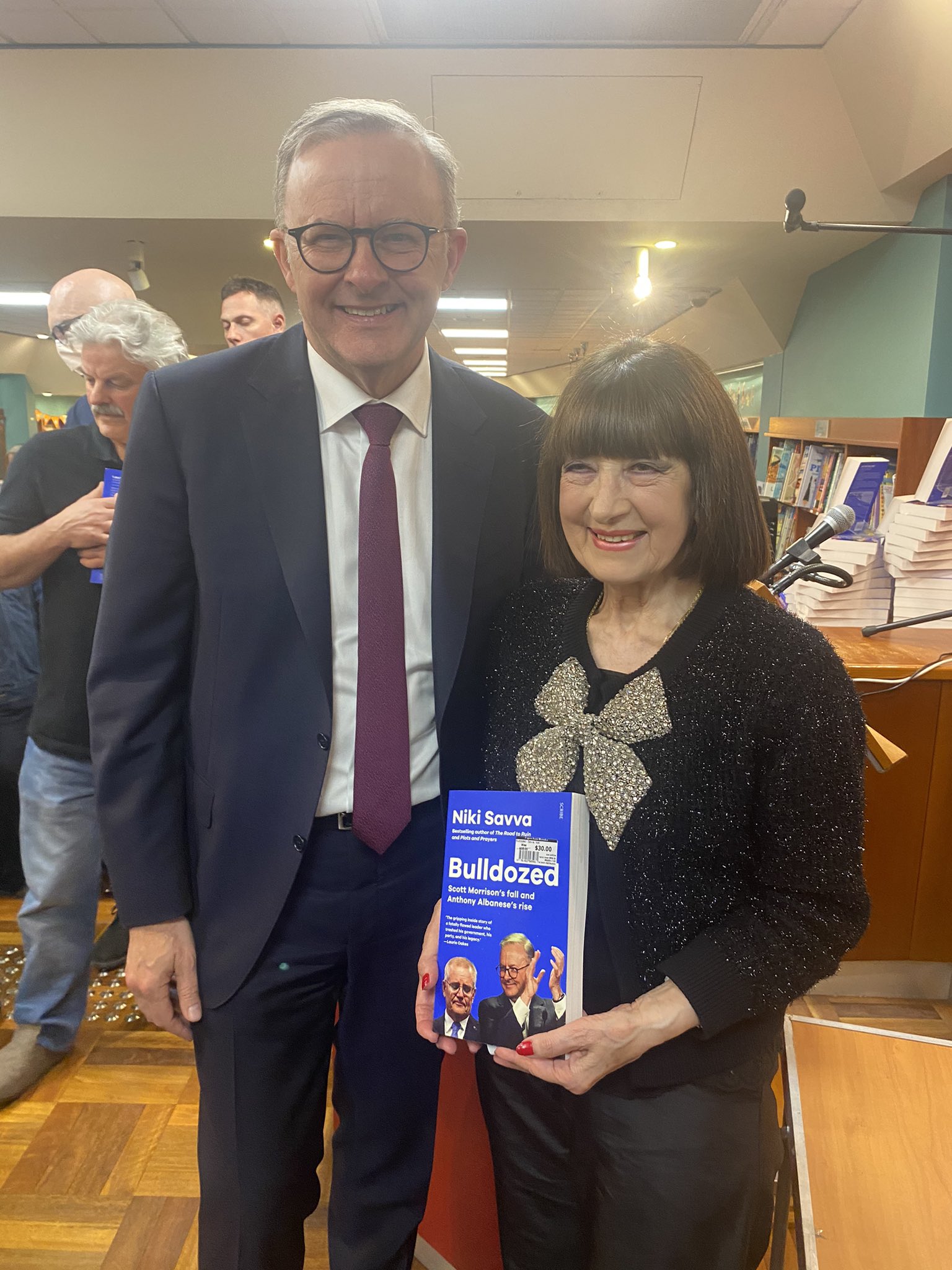

Laurie Oakes launched Niki Savva’s new book Bulldozed on 1 December to a sold-out event at the Paperchain in Canberra. Here are the transcripts of both Laurie’s launch speech and Niki’s speech from the night.

There are obvious similarities between McMahon and Morrison, the most obvious being that neither of them was troubled by a slavish commitment to the truth.

—Laurie Oakes

Laurie Oakes

It is my great pleasure this evening to launch the final instalment in Niki Savva’s terrific trilogy. The three books cover a trinity of Liberal prime ministers, but — despite plenty of references to praying and laying on of hands and other forms of God-bothering, particularly in this latest volume — it’s certainly not a holy trinity.

Having exposed Tony Abbott’s constant and cocky stupidity and strange dependence on a staffer in The Road to Ruin, and demonstrated that Malcolm Turnbull is very often NOT the smartest person in the room in Plots and Prayers, Niki shows in Bulldozed why Scott Morrison’s only real legacy appears to be a debate about whether he proved himself a worse prime minister than Billy McMahon.

That debate is reflected on the back cover of the book. I’m about to have my say now. It’s topical because tomorrow is the 50th anniversary of McMahon’s political defenestration by the voters. Otherwise known as the 50th anniversary of the election of the Whitlam government.

Before I start pontificating about the 2022 federal election and the literature it has inspired, I’d like to touch briefly on that other poll half a century ago because it helps to explain why I am so pleased to be doing the honours for Niki tonight.

I spent election night 1972 with Gough Whitlam. I was at the party for Labor supporters and campaign workers at the Whitlam home at 32 Albert Street, Cabramatta. And I was at the Sunnybrook Motel two blocks away when Whitlam snuck off there with members of his family and some staff for a couple of hours to watch the results come in.

I vividly remember the moment Gough knew for sure that he had won. There were no computers back then. Just Mungo MacCallum and a calculator. At 9.20 pm Mungo jabbed the buttons on his machine a couple of times, then looked at Gough and announced: ‘I think we can send the white smoke up the chimney.’ It was a genuine moment of history, and I felt very privileged to be there.

I had that access because, with David Solomon, I was writing a book called The Making of an Australian Prime Minister. I think it’s accurate to say it was the first Australian book of its kind. That is, books that examine an election, the events leading up to it and the characters involved.

There had been such books in America before that, but not here. There have been quite a few since, though, and with Bulldozed, Niki makes another distinguished contribution to the genre.

I mentioned the argument over our worst prime minister. Until now I’ve not been in much doubt that the honour goes to Billy McMahon. But after recent events, and particularly after reading Bulldozed, I think I have to acknowledge that Scott Morrison deserves the title of ‘Worse PM Than Billy’. And by a sizeable margin.

It’s true that Scott Morrison didn’t have McMahon’s gift of the gaffe. Billy went through the 1972 campaign saying things like: ‘We will honour all the problems we have made.’ But Morrison did give us memorable visual gaffes. Like crashing a children’s soccer game and bulldozing an eight-year-old boy into the ground.

At the time of that incident, we didn’t know that Morrison had appointed himself to five extra ministries without telling anyone. But we know that now — and we know that he’d been eyeing off at least one other portfolio. I notice someone tweeted just last week that the kid was bloody lucky he wasn’t mown down by an entire cabinet.

There are obvious similarities between McMahon and Morrison, the most obvious being that neither of them was troubled by a slavish commitment to the truth.

One of McMahon’s nicknames was Billy Liar. You couldn’t trust a word he said. But Niki writes in Bulldozed: ‘Morrison would lie, get caught out, and then he would deny that he had lied, pretending it never happened, rarely if ever apologising for it, seemingly incapable of admitting it even to himself.’ And no French president ever called McMahon a liar.

But I think there’s a more interesting similarity between Morrison and McMahon. It has to do with the secret ministries, and it leapt out at me as I read Niki’s book.

Possibly the biggest news story of the 1972 election campaign was McMahon dumping on his cabinet in a television interview. He said that as prime minister he had wanted to be the head of a team. And he’d wanted to delegate authority to relevant ministers. But this had not worked out because ministers did not get things done as quickly as he expected. He also frequently found that the political approaches of ministers were not as good as he thought they should be. As a result, McMahon said, he had to make more decisions himself than he’d intended.

Morrison’s motivation in secretly giving himself authority to administer all those portfolios, with even the incumbents being kept in blissful ignorance in all but one case, was clearly similar. He didn’t trust his team. It is the only explanation for his bizarre actions that makes any sense at all. He wanted to be in a position to over-rule ministers or take over from them, or at least keep a close eye on them if he felt the need. In Niki’s words: ‘A power-hungry control freak who lacked confidence in his own colleagues’.

The explanations Morrison himself has given — even to the Bell inquiry or to parliament — are implausible and contradictory. Former High Court judge Virginia Bell made it clear she didn’t believe him. I don’t see how anyone could believe what he trotted out in the censure motion debate yesterday. It was simply embarrassing.

But where Billy merely vented on television a few days out from an election, thereby generating massive headlines exposing to public gaze the shambles his government had become, Morrison devised a devious method of dealing with his lack of trust in ministers — a method that undermined the principles of responsible government. This illustrates the big difference between the two.

By the time he got to The Lodge, McMahon was into his dotage. A bungler, a fool, a figure of fun. There is nothing funny about Scott Morrison. In fact, in Plots and Prayers — and she probably won’t thank me for reminding people of this — Niki herself described Morrison as ‘the most astute conservative politician of his generation’. He has to be taken seriously, and what he did has to be taken seriously too.

Morrison’s actions in this sorry saga are certainly not on a par with what’s happened in the US. But they are a step — a small step — down the same road American Republicans have travelled under the influence of Donald Trump.

I’ve had a fair bit to do with political books recently.

With Laura Tingle and John Warhurst, I was a judge for the inaugural Australian Political Book of the Year Award. Announcing the winner and presenting the award, Treasurer Jim Chalmers commented that people say things for a book they’d never say for a weekend newspaper piece.

He’s right, and one of the great strengths of Bulldozed, as well as the two Savva books that preceded it, is the way Niki gets people to talk on the record. There are some anonymous sources, sure. But to a remarkable extent, people put their names to their words. The frankness — the willingness to be quoted — is just as evident from the Labor side as from the coalition.

This gives Niki’s work credibility and authority.

In Bulldozed, Josh Frydenberg is remarkably frank, especially on how he feels about his alleged friend Morrison moving in on his Treasury portfolio without his knowledge. Even closer Morrison mates, Stuart Robert and Alex Hawke, don’t hold back in their criticism of him.

Jim Chalmers also said politicians often have regrets about what they say to the writers of books. He’s right on that, too. Alex Hawke had a case of the regrets about his quotes in Bulldozed earlier this week. But he didn’t actually deny them.

There are lots of other reasons to like this book.

There’s the wit. Morrison, for example, is described as ‘Boris Johnson without the hair or the humour’. And this line: ‘It was quintessential Morrison … Allow a problem to become a crisis before mishandling it.’

There’s vivid writing. Like: ‘Hanging over it all like a dark mist was Morrison.’ And: ‘Even though they could see the ship heading straight for the iceberg they did not mutiny. Instead, they waited on deck without lifejackets, without lifeboats, for their captain to ram it.’

There’s also good, old-fashioned journalism. A case in point — Niki digs out stuff on the so-called Mean Girls saga that corrects some of the crap that appeared in the media at the time. She also has fascinating material on Anthony Albanese’s preparation for the election debates. She digs deep on the extraordinary failure of the NSW Liberal Party to preselect candidates until the election campaign was upon them. There’s terrific material on the Teals. And so on.

Niki always was a news-breaker, and she breaks plenty of news here, as we’ve seen from the extracts that have already appeared in newspapers.

One of the things you want from a book like this is some discussion of aspects of our political system that might need attention, warnings of any problems in the operation of our democracy. Bulldozed certainly delivers on that. Especially on a matter we’re normally pretty wary about discussing in a political context.

I refer, of course, to God.

Niki writes of a minister who kept a musical keyboard in his office so that he could call in his staff to sing hymns. She reports a prominent senator’s complaint to colleagues that Morrison wanted to turn the entire NSW Liberal Party into a branch of Hillsong. She quotes a Liberal MP saying Morrison ‘thought starting a religious war would provide an alibi for a failure to have an economic narrative’. She reveals worry among some Liberals, Christians themselves, that praying became a substitute for good political practice in the Morrison government. She quotes a former cabinet minister saying Morrison had a thing about God having chosen him to be prime minister.

What Niki writes about, plus some of what emerged about the influence of religious hardliners in the lead-up to last weekend’s Victorian election, shouldn’t be ignored if we’re to have a healthy democracy: religious nutters as candidates; the weaponising of religious faith for political purposes; prayer threatening to replace proper policy development; and the possibility that a political leader believes he is anointed by God.

Niki even quotes a prominent Liberal saying Morrison would only step down if God told him to. God never did — though he might have if he’d read Niki’s book.

How do we deal with the problem, though? I think the only way is to stop tip-toeing around it. Religion and its influence on politics needs to be treated like any other issue. It can’t be a no-go area. Niki, among others, has now shone a light on it. The Victorian election produced more reason for concern. We’ve just got to stop being shy about discussing it, writing about it, investigating it.

One more mention of Billy McMahon … I can’t seem to get away from the little bastard … He once remarked: ‘Sometimes I think I’m my own worst enemy’. Quick as a flash Jim Killen, a Liberal MP and former minister interjected: ‘Not while I’m alive.’

Well, one of the things that strikes me about Bulldozed is the extent to which Scott Morrison really was his own worst enemy. Over and over again, he brought trouble down on himself.

The ministry grab that has ensured a humiliating and smelly end to his political career would have remained secret, and the whole damaging row would have been avoided, if he had kept his trap shut. The authors of Plagued failed to twig to the full implications of the hint he gave them when boasting about how clever he’d been in the pandemic. But other journalists started digging when the book came out, and the jig was up.

Then there was the Hawai’ian holiday while bushfires raged at home. The decision to lie about the trip guaranteed there would be a damaging story, but Niki shows how Morrison’s urge to show off poured petrol on the flames, so to speak.

Chatting before recording a 60 Minutes interview with Karl Stefanovic, Morrison volunteered the information that he was learning the ukulele. That was silly enough, but at least he had the sense to say ‘No’ when Karl asked him to demonstrate on camera. After the interview, though, and after cooking a curry for Karl and the crew, he rushed off unasked to get the ukulele anyway, and — as Niki puts it — ‘chose to strum an instrument that the whole world associates with Hawai’i’. Karl couldn’t believe his luck. Nor could Labor, presumably.

And there were the short, sharp, punchy lines that came out of Morrison’s mouth and proved deadly for him. Niki reveals that Simon Birmingham, now Senate opposition leader, called them Morrison’s ‘suicide notes’. You all know them. ‘I don’t hold a hose, mate.’ ‘It’s not a race.’ And: ‘It’s not my job.’

You have to wonder whether, on top of those extra ministerial positions he’d secretly taken on, Morrison had also contracted confidentially to work for the opposition.

It was all a great help to Labor, given that Anthony Albanese’s strategy was to make the election a referendum on Morrison’s character. A strategy presumably based on the well-known fact that, when there’s a referendum, Australians almost always vote NO.

A final point. Niki touches on the behaviour of the media in the campaign. And there was a fair bit of criticism of it — particularly at a news conference where Albo was yelled at, and — as Niki describes it — ‘the questioning was feral, hysterical’. But if you want to put the 2022 press pack in context, let me take you back to Albert Street, Cabramatta, 50 years ago tomorrow night as the new prime minister is about to hold a press conference in the small sunroom of the small cottage.

This is what David and I wrote:

Radio and television reporters are scuffling among themselves and with party guests to get close to the doorway. A huge bearded man from the ABC is trying unsuccessfully to move the crowd aside to clear the area in front of the camera which will take the event live across Australia. ‘Get your hands off me,’ an angry photographer in a pink shirt snarls at a television reporter. Punches are thrown. Blood spurts from the nose of a radio journalist. ‘Come on, simmer down,’ people shout … More punches are thrown. ‘Go to buggery, punk,’ the photographer screams at a member of the ABC crew. ‘This is not the ABC studio.’ … Tony Whitlam, the 6 foot 5 inch son of the Labor leader, moves in to try to break up the scuffles … A Whitlam aide, Richard Hall, places a hand on his shoulder and says: ‘Easy, Tony.’ David White motions to a rather large member of the Canberra press corps, and whispers, ‘Stand in the doorway and look imposing while I get some policemen.’

It is, I think, yesterday’s media hacks saying to today’s media hacks: ‘That’s not a knife. This is a knife.’

Now, please behave yourselves as I declare Bulldozed launched.

Niki Savva

Thank you, Laurie, and thank you, Henry. My thanks to all of you for coming tonight.

This is the fourth time in 12 years that the three of us have stood together in this same spot. For a while there, it looked like the third time would be our last.

Henry had to twist my arm to get me to write Bulldozed, then I had to twist Laurie’s to get him to launch it, and he came up with the title as well. I am very lucky to have such clever, generous friends.

There were moments I believed I would never write about Scott Morrison’s downfall, something that half of me was desperate to do while the other half dreaded it.

I was only ever going to write another book if Morrison lost the election. Then I dreaded it because I knew what it would involve. Just like The Road to Ruin and Plots and Prayers, I felt like a first responder to a crime scene, with the grisly task of trying to sort through the wreckage, the blood, and the lies in an effort to nail the prime suspect, the one who dismembered the Liberal Party.

In the other two books, the leaders were eliminated by their own MPs because of their perceived transgressions or failings. In Bulldozed, the troops stuck by the leader to the bitter end. He repaid their loyalty by stealing their portfolios and leading them into the wilderness.

By his own actions and with his own words, he damaged them, possibly irreparably, and disgraced himself. They stood by him, then covered up for him, and — except for a few honourable exceptions — continue to protect him now, oblivious to the harm they are inflicting on themselves and on the parliament.

Whilever he remains in parliament, Scott Morrison is a reminder of everything that went wrong with a government which managed to alienate women, Chinese Australians, business, young people, environmentalists, and seniors who had never in their lives voted for any other party.

Morrison never stopped blaming others, even God, for whatever went wrong, which was quite a lot.

He lied early and often, without compunction or shame. He is incapable of saying sorry and sounding like he means it, or of accepting responsibility for his own actions.

The most effusive apology for his flight to Hawai’i during the Black Summer bushfires, which many of his colleagues believe was the beginning of the end for his leadership — and I agree with them — did not come from him. It came from his wife, Jenny, on 60 Minutes.

So after spending three years writing about his woeful prime ministership, if Morrison had won on May 21, there would have been nothing left for me to say, or to write.

But Australians worked him out. They saw through him. They were smart enough to know how to dispose of him and how to send everybody else a message that they had to do better.

May 21 affirmed my faith in the ability of Australian voters to get it right, and in the wisdom of our compulsory preferential voting system.

Still, in the lead-up there was always a part of me that felt Morrison might win again. Partly because I was uncertain how Anthony Albanese would handle a campaign.

Albanese’s mistakes on that very first day were costly, but he didn’t get where he is by folding after copping a beating. Even a self-inflicted one.

As he says, he is both tough and resilient.

While he showed his mettle by refusing to allow that day to overwhelm him, his comeback was forged by an amazing team effort. Good personal staff, good frontbenchers, and good party officials were critical to his recovery and to his success.

Albanese is smart enough to surround himself with very smart people, then clever enough to take their advice. Another welcome aspect of Albanese’s personality and his leadership is that he knows who he is. He doesn’t play at being a hairdresser one day, a welder the next, a lab assistant the day after, or a child soccer player the day after that.

In Bulldozed, I said that at 100 days in office it could have been Albo of the thousand days because he had slipped into the job so smoothly. Partly that’s because he is concentrating on being prime minister.

I could say thank God for that.

But I don’t believe God decides who wins and who loses elections by directing the hand of each and every voter at the ballot box.

Too often, Morrison not only failed to understand or appreciate what Australians expected of their prime minister; he allowed religion to influence his behaviour. He used it as both a weapon and a crutch.

There are a collection of quotes from him, a few of them delivered at times when Australians needed him most, that showed a repeated failure to appreciate the gravity of situations he created or confronted and what he needed to do to fix them.

‘I don’t hold a hose, mate’, ‘That’s not my job’, and ‘It’s not a race’ summed up his view of life and leadership. Telling women they were lucky they weren’t being shot for protesting on the streets was another doozy.

Morrison’s snappy lines became the shortest political suicide notes in history.

Another very revealing quote, which I record in Bulldozed, came after five of his own backbenchers — Bridget Archer had company for a change — finally stood up to him, forcing him to retreat on his religious discrimination bill.

The one that actually would have allowed discrimination against vulnerable kids.

Filled with self-pity, he cast himself as the victim and absolved himself of responsibility. He said to his colleagues afterwards, ‘I have been mocked every day because of my faith, because I am a Pentecostal.

‘I have surrendered this battle to God, now. I have said, over to you.’

A few weeks later, he chose Katherine Deves to run for Warringah in what many Liberals saw as an attempt to harvest the votes of the religious right in western Sydney.

He failed there, but he succeeded in ensuring that moderate Liberals in heartland seats lost their seats to exceptional — mainly women — independents, who challenged them.

He inflicted immense damage on the party’s reputation and its capacity to represent a broad cross-section of Australians, to the point where some moderates now fear that the Liberal Party will struggle to survive.

A few people might believe this was in fact God’s response to Morrison’s surrender to him. Not Morrison. In a sermon in Perth after the election, he urged people not to trust in governments, implying that the election result was all part of God’s grand plan for him. Again, none of it was his fault.

Morrison had devoted most of his life to getting himself and others elected, often using the dirtiest or most deceptive tactics. Not content with that, he secretly acquired the portfolios of his most senior ministers without telling them. Or us.

On one level, his remarks in that sermon were deeply offensive. On another, it proved his point that some governments, some prime ministers, just can’t be trusted.

There are very few treasurers who were as loyal to their prime ministers as Frydenberg was. I struggle to name one.

Morrison’s unpopularity, when combined with Monique Ryan’s campaign, ensured that Frydenberg lost Kooyong.

Morrison repaid Frydenberg’s fidelity by covertly taking over Treasury; then, even after Albanese exposed the depths of his deception, Morrison told Frydenberg he would do it again if he had his time over.

He remains incapable of understanding that what he had done was profoundly wrong both politically and morally. He still refuses to accept that what he did fundamentally undermined parliamentary democracy.

It is puzzling to me that a person who claims to hold such profound religious beliefs can be so casual with the truth and so careless with his relationships.

He was the worst prime minister I have covered, and I have written about all of them since Gough Whitlam, rest his soul, who was elected 50 years ago tomorrow.

Now there was a prime minister not frightened to leave a legacy.

You would think after all these years that I would know better, but as the first columnist to write that Morrison would one day lead the Liberals, I apologise, again, for whatever part I played in the creation of Scott Morrison as prime minister.

I sought to make up for that lapse in judgment by sharing with people what I had come to realise, that he was a deeply flawed character not up to the job.

But he managed during his reign to inflict considerable damage on the body politic.

That is his legacy, the one he claimed he never wanted. Constitutional lawyer Anne Twomey, who is not prone to exaggeration, called it poisonous.

Like the other books, this one could not have been written without a lot of help.

My deepest thanks to all those who spoke to me either on the record or on background. Without them, most of whom are named in this book, and some of whom are here this evening, it could not have happened.

I want to thank my husband, Vincent, for his unwavering support, and my immediate family, who unfortunately could not be here tonight, for loving me no matter what.

I am so grateful to my friends Elissa, Lizzie, Kerry-Anne, Laura, Sue, Lajla, and so many others for their encouragement and faith in me. Huge thanks to Matt for his technical expertise and to Jessie for the caffeine hits and the good cheer.

Thanks to Henry and to everyone at Scribe, including Cora Roberts for making travel and so much else not just easy but enjoyable.

Thank you to Paperchain for hosting for the fourth time.

I am loathe to say that Bulldozed will be my last book, but I have promised several people that it will be.

Also, I can’t at the moment envisage the circumstances that might warrant another.

Mind you, friends and family have heard me say similar things before — so, sadly, it’s not only politicians who break promises. But because we are all getting on, because nothing lasts forever, goodbye, farewell, and amen. And that’s a quote from M*A*S*H, not Morrison.

Niki Savva

Niki Savva is one of the most senior correspondents in the Canberra…

Discover